My Prophylactic Mastectomy: What Led Me to Go Under the Knife

I woke up from anesthesia two months ago, certain that I made the right choice to undergo a bilateral prophylactic mastectomy for a faulty breast cancer gene. I snapped a quick selfie, unadorned and very raw, in my hospital bed and wanted to share it with you (see photo).

I woke up from anesthesia two months ago, certain that I made the right choice to undergo a bilateral prophylactic mastectomy for a faulty breast cancer gene. I snapped a quick selfie, unadorned and very raw, in my hospital bed and wanted to share it with you (see photo).

Breasts are an important symbol of so many things: nurturance, femininity, and sexuality. My breasts have served me well over the past 50 years. They hosted the kickoff party in puberty. They’ve been an important part of my sexual identity. I breast fed two daughters for nearly one year each. They’ve gone up and down in size as my weight fluctuated. Yet for all the joy they bring, breasts can also turn against us as we’ve seen in the epidemic of breast cancer. By the year 2030, new cases of breast cancer are expected to rise by 50 percent.[1]

Fifty percent? Unfortunately, that grim statistic fits with what I’ve diagnosed and witnessed in my female patients over the past 25 years as a gynecologist who practices precision, integrative, and functional medicine.

You may wonder why I chose something as drastic as surgery, when I believe in the power of epigenetics to turn genes on and off to one’s advantage. The answer requires a brief back-story.

Apparently I’m a Previvor

While writing my latest book, I discovered I had a mutation of the gene CHEK2 (see page 22-23 of my latest book Younger for more details.). That makes me a “previvor” in the new parlance of breast cancer. (“Previvors” are people who are survivors of a predisposition to cancer but who haven’t had the disease. This group includes individuals who carry a hereditary mutation, a family history of cancer, or some other predisposing factor.) Discovering the mutation made it difficult to feel whole. I have other genes that cause me to make more dangerous estrogens, the type that cause DNA mutations and increase the risk of breast cancer (more on that in a minute), and I haven’t been able to silence them despite my best efforts and protocols.

As I gathered information about CHEK2 and whether screening or surgery made the most sense, friends, family members, personal and professional experience, and the media certainly influenced my decision. A relative underwent mastectomies for another faulty gene. When I saw her next, she hiked up her shirt to show me her gorgeous new breasts post prophylactic mastectomy. Certainly, Angelina Jolie raised controversy with her gene mutation and then going public in a New York Times Op-ed about her prophylactic oophorectomies and mastectomies to reduce her risk of breast and ovarian cancer.[2] While there were some positive role models, I wanted to make my decision based on the latest data and from a whole, integrated place.

My Gene Mutation: CHEK2

CHEK2 is a tumor suppressor gene, similar to BRCA1 (from “BReast CAncer gene one”) and BRCA2 (from “BReast CAncer gene two”) that I write about in Younger: A Breakthrough Program to Reset Your Genes, Reverse Aging, and Turn Back the Clock 10 Years. In 2002, researchers discovered that a gene mutation of CHEK2 confers a greater risk of breast cancer in 2002, so we now have fifteen years of data and experience to draw from. Tumor suppressor genes repair cell damage and breaks in DNA in order to keep breast cells growing normally. When you inherit the variant, you may not be able to prevent breast tumors from forming.

Because of my genetic mutation, I’m less likely to suppress cancer in my breast or colon like someone with the normal CHEK2 gene. Overall, CHEK2 is a moderate risk gene, with 2-5 times increased risk of breast cancer and 2 times increased risk of colon cancer.[3]

Overall, one in four women with breast cancer have a gene variant. There are thousands of variants of these breast cancer genes and probably another hundred other breast cancer genes (such as TP53, PTEN, ATM, and PALB2).[4] For women with BRCA1 and BRCA2, the range in risk is broad: 20 percent in some people, and 90 percent in others, which means out of one hundred women with the BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, somewhere between twenty to ninety will develop breast cancer. Without intervention (e.g., targeted epigenetic change, including preventative surgery), a woman with a BRCA gene mutation is seven times more likely than other women to get breast cancer (and thirty times more likely to get ovarian cancer) by age seventy.

As I went through eight months of genetic counseling, meeting with breast surgeons in the High Risk Breast Clinic and discussing reconstruction options with multiple plastic surgeons, one thing was perfectly clear: I’d rather be with my family than with my breasts as potential cancer-making factories.

Another Gene Variation That Affects My Estrogen Levels: CYP1B1

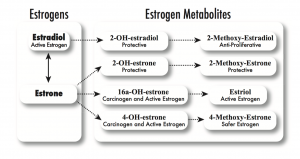

On top of my discovery of the CHEK2 mutation, I’d already known I was at higher risk for breast cancer. In 2006, I started checking my estrogen metabolism, or how I produce, use, and get rid of estrogens, both the protective types and the dangerous and provocative types—in my body. See the illustration below from page 156 of my first book, The Hormone Cure, for the estrogen metabolism pathways.

Estrogen metabolism occurs primarily via four pathways, starting either with estradiol or estriol. Some studies have found that a relatively high ratio of 2:16 (2-OHE to 16-alpha-OHE) is associated with a lower breast cancer risk, which reflects dominance of one pathway over the other.

I discovered that I don’t metabolize estrogen well: I make too little of the protective types (2-methoxy-estradiol, 2-methoxy-estrone, and estriol) and too much of the dangerous types (16-alpha-hydroxy-estrone and 4-hydroxy estrogens, particularly 4-OH estrone), putting me at higher risk of breast cancer. I checked my genome and found that I have a variant in CYP1B1, which predisposes me to more of the 4-hydroxy estrogens.

So I did what I recommend to my patients: I attempted to put epigenetics to work. I began eating more cruciferous vegetables and fiber, stopped drinking wine, and started taking di-indole methane (DIM) and calcium diglucurate. Then I retested. My results barely budged. I was able to improve my 2:16 ratio, but not my 4-hydroxy pathway. It turns out the 4-hydroxy pathway is difficult to modulate with lifestyle change. After trying for eleven years, I ultimately decided the prophylactic mastectomy route was the best option for my particular situation.

If you are wondering about your estrogen metabolism and genetics, I recommend that you work with a functional medicine clinician,[5] and consider ordering the Precision Analytic DUTCH test or Genova’s Complete Hormones Test (or similar urine test),[6] and their Estrogenomics profile.[7] (Note: I have no financial ties to any of the lab companies mentioned in this blog.)

Yes, There’s Controversy

Along the way, I’ve been dismayed at how some surgeons dismissed me, perhaps because they were unfamiliar with my gene mutation or maybe because of the high rate of complication associated with mastectomy—in the range of 27 percent. One plastic surgeon thought I was making a poor choice, one she would never make because she doesn’t believe in the gene-environment interaction! (Huh?) Another breast surgeon said to me, “Sara, why not screen with MRI? We have gotten better at diagnosing breast cancer earlier.” While that may work for some women and be preferred to the more drastic surgical option I chose, I consider cancer to be a failure state of physiology. And I’m more likely to have a failure state because my checkpoints are not normal. On the other hand, I strongly encourage other women with genetic mutations to talk in detail with their clinicians about which choice is right for them. I encourage screening with MRIs and mammograms if it aligns with your risks, values, and circumstances.

A friend of mine who was recovering from bilateral mastectomies for a diffuse precancerous state of the breasts called lobular carcinoma in situ said to me, “I don’t want to die of breast cancer; I’d rather die of something else.”

I agree. I’ve taken care of hundreds of patients with breast cancer, from diagnosing new lumps to counteracting chemo brain to witnessing the final breaths of women with metastatic disease. I made my decision not from fear, but from love.

So I chose to work with a surgeon whose worldview fit better with mine, who felt more collaborative and who has a long history of immediate reconstruction, which means a single surgery. He warned me, though, that 20 percent of the time it doesn’t work because of compromised blood flow. I fell in that 20 percent, so right now I have tissue expanders in place. My new breasts still look weird. I feel like my task is to just embrace the weird. They will hopefully look better after my follow-up surgery!

Recovery and Healing

The recovery includes what you’d expect—fatigue, surgical drains, soreness and numbness in my chest, loss of mobility in my pectoralis muscles, swelling, and so much sleeping—but those things pale in comparison with the relief I feel about reducing my risk of breast cancer from upwards of 60 percent down to less than 1 percent.

Right now, I’m focused on healing—what it is, what it isn’t, what matters, what doesn’t. You’ll be hearing less from me, but I’m still thinking about you as I nap and shuffle around, performing post-mastectomy range-of-motion exercises.

Special thanks for my husband, who has been so calm and witty every step of the way. He doesn’t mind the smell of burning moxa (a heat therapy from Chinese medicine) coming from our bedroom as I try to improve my blood circulation post-op. He makes breakfast, lunch, and dinner for me and makes sure I’m not pushing too hard as I return to exercise. I’m grateful to my daughters who’ve helped with washing my hair after surgery, which feels so tender and sweet. Thank you to my friends and family who’ve cooked meals for me and lounged next to me on the bed, catching me up on their lives.

I understand that reading about such a controversial choice may make many women uncomfortable. I encourage you to transmute that discomfort into something productive. Take care of your breasts by eating risk-reducing vegetables, minding your insulin, and lowering your consumption of alcohol. Learn more about your genetic risk by running your genetic profile at 23andme.com or better yet, consider joining The Wisdom Study. The study is enrolling 100,000 women in various locations in specific states between the ages of 40-74. It’s run by a breast surgeon whom I highly respect named Laura Esserman MD, head of the Breast Cancer Center at the University of California at San Francisco. Designed to end the confusion around breast cancer screening, study leaders are comparing two safe and accepted screening recommendations: routine annual screening mammography, or a personalized screening schedule including genetic testing for breast cancer risk. I believe this is a great way to look at the old population-based model compared with personalized medicine, and I’ve enrolled in the study. You know how I feel about research, so this is your chance to become part of history. You can place your name on a waitlist when you enroll. (Update from 11/10/20: Wisdom is still enrolling! I am a volunteer ambassador so learn more now! We have 31,053 women enrolled, so only 68,947 to go. Please join us!)

The Right Decision for Me

Not everyone will agree with my decision, but it was the right decision for me. My hope is that my experience will help other women make informed, wise, highly personal decisions about their own health, breath or otherwise. I believe in personalized medicine, where you know about some of your more scary genes and how they dance with environmental influences, and thereby choose wisely based on that information. Allow knowledge to trump fear.

Now on the other side of surgery, I know that the best way to face death is to celebrate life. I have total clarity, peace, and joy about my decision. I have one more breast surgery next month and while I don’t want to face the knife again, it is the right decision.

I want to thank my friends, family, and tribe for their outpouring of love and support while I’ve been in bed, recovering.

My decision is small in the larger scheme of decisions women face as they try to prevent and treat breast cancer. As we head toward personalized medicine based on the interaction of our genes with our environment, we will each be facing decisions like this one.

Thank you again for your love and support! It means the world to me as I allow the healing to continue.

________

[1] “U.S. breast cancer cases expected to increase by as much as 50 percent by 2030.” American Association for Cancer Research, accessed April 30, 2015, www.aacr.org/Newsroom/Pages /News-Release-Detail.aspx?ItemID=708#.VUJpv61VhBc; Brown, E. “Breast cancer cases in U.S. projected to rise as much as 50% by 2030.” Los Angeles Times, April 20, 2015, accessed April 30, 2015, www.latimes.com/science/sciencenow/la-sci-sn-breast-cancer-cases-2030 –20150420-story.html.

[2] Jolie, A. “My medical choice,” New York Times, May 14, 2013, www.nytimes.com/2013/05/14 /opinion/my-medical-choice.html?_r=0. Jolie, A. “Diary of a surgery,” New York Times, March 24, 2015, www.nytimes.com/2015/03 /24/opinion/angelina-jolie-pitt-diary-of-a-surgery.html.

[3] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18172190

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27716369

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20597917

[4] Walsh, T., et al. “Ten genes for inherited breast cancer.” Cancer Cell 11, no. 2 (2007): 103–5; Walsh, T., et al. “Spectrum of mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, and TP53 in families at high risk of breast cancer.” JAMA 295, no. 12 (2006): 1379–88; Alorai , F., et al. “Gene analysis techniques and susceptibility gene discovery in non-BRCA1/BRCA2 familial breast cancer.” Surgical Oncology 24, no. 2 (2015): 100–109; Lee, D. S. C., et al. “Comparable frequency of BRCA1, BRCA2 and TP53 germline mutations in a multi-ethnic Asian cohort suggests TP53 screening should be ordered together with BRCA1/2 screening to early-onset breast cancer patients.” Breast Cancer Research 14, no. 2 (2012): R66. For lay audiences, these citations may be helpful: “Genetics,” BreastCancer.org, accessed February 13, 2016, www.breastcancer.org/risk/factors/genetics; “Inherited gene mutations,” Komen.org, accessed February 13, 2016, http://ww5.komen.org/BreastCancer/InheritedGenetic Mutations.html; “Breast cancer genes,” Cancer Research UK, accessed February 13, 2016, www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/type/breast-cancer/about/risks/breast -cancer-genes

[5] https://ifm.org/find-a-practitioner/

[6] https://www.gdx.net/product/complete-hormones-test-urine

[7] https://www.gdx.net/product/estrogenomic-genomic-testing-saliva